F is sitting with you. She holds your hand as your breathing slows. She is your eldest, and she has come from farthest away. Where has she come from? Oh yes, North Carolina, that’s right. That’s the far side of the country. Shouldn’t she be back there now, looking after her grandkids? Your great-grandchildren.

Wait, what? How is it possible you have great-grandchildren? You can’t possibly be old enough for that. It was just the other day that you were visiting with your cousins Beryl and Kathryn at Uncle Ted’s house, and Aunt Elsie and cousin Annie were there… no, that was a while ago, but you’re not exactly sure how long. It feels like just last week that you all played together as children, and then you recall Aunt Elsie saying she was to be called Kathleen now, not Elsie, she always hated that name, and there sure are a lot of Kathryns and Katherines and Kathleens in the family, you always thought Elsie was distinctive, but there it is.

Uncle Ted and Aunt Elsie are there, they’re smiling, happy to see you, and there alongside them are Father and Mother. You just need F to let go your hand, and you’ll go to join them now. Your breathing relaxes and slows.

It is two weeks earlier, and you’re dizzy.

Is he an Aussie, is he, Lizzie?

Is he an Aussie, is he, eh?

Is it because he is an Aussie,

Does he make you dizzy, Lizzie?

You keep having dizzy spells, and your head hurts, though you’re not sure why. You fell and hit your head against the door jamb, J says, and that’s why you shouldn’t drive anywhere right now — but the song makes you feel better, so you sing it out loud. It’s a popular hit right now, but for some odd reason the others don’t seem to know it. They smile, but the smiles seem a little strained.

It was a pop hit in the 1940s, when you were a teenager in New Zealand. The others are your children, and they were not yet born.

M is in the dining room, working on his laptop. He seems to be working quite a lot, that boy. So much work, he has two laptops. You go and sit at the table across from him and look at the papers he has spread around. These sure look like important papers, with things like State of California and Citibank and so forth strewn across their headers. The piles aren’t very neat, though. You’ll just help M out a little. He works too much anyway. You pick up one pile and straighten the edges, and then you see your own name at the top of the first page.

That’s odd. That looks like a legal document. Revocable Living Trust, it says, but you don’t recall having a trust. And this other one, it appears to be paperwork for your mobile home. And that one, that’s your bank statement.

These have my name on them, you say.

That’s right, M replies. I’m just helping you to get everything in order.

In order for what?

Just in case. You need a little help right now, so J is assisting you, and I’m assisting her by taking care of paperwork. I want to thank you, Mother, for keeping such orderly files. That makes this much easier. But why didn’t you tell anyone about your finances before?

You’re children. You didn’t need to know.

Your son is 54 years old. J, your youngest, is 49. They are not children, but they always will be to you. It bothers you that M is rifling through your private papers. You leaf through the nearest pile. M watches, looking a little strained.

D comes into the room. Mother, let’s go watch some television, shall we? We’ll find a Clint Eastwood movie. M needs to work.

He sure works a lot, you say. You don’t recall what he’s working on, or why it’s so important, so you go with D. You stumble on the three steps down the short stair into the living room, and reach out for a handhold. You grab onto the cat tower, and it nearly tips over, but doesn’t quite.

D looks stricken. What on earth is wrong with her, you wonder? Everyone seems to be acting strangely. Ah, you know just the thing to liven up spirits. How about the latest pop song?

Is he an Aussie, is he, Lizzie?

Is he an Aussie, is he, eh?

Is it because he is an Aussie,

Does he make you dizzy, Lizzie?

You’re looking for your car keys. You’re certain they’re here somewhere, but they aren’t in your pocket. What’s wrong, Mother? D asks.

Where are my keys?

Mother, you can’t drive. Your keys are safe, but you don’t need them right now.

Nonsense. It’s time I got out of everyone’s hair. I’ll just drive myself home.

Mother, you can’t. You need to stay here. It’s not safe for you to drive. It’s not safe for you to be alone.

Why not?

D looks around for a moment, then she picks up a piece of paper and hands it to you. It’s enclosed in a thin, clear plastic sheath, and it has large-font typing on it. It’s a bit crumpled, as if it has been brought out quite a few times.

Mother, you have a brain tumor. The tumor is affecting your memory. It is also affecting your motor control. This tumor makes it unsafe for you to live alone. So, you are now living here at R and J’s home in San Mateo. All of your children are here to visit you. We love you. You are safe. — F, D, M, J, and R

You look at D. Brain tumor? How do you know that?

You had an MRI, and a CT scan, a week and a half ago. Your doctor and your neurologist both reviewed them. It’s very clear.

Huh. You shrug. But where are my keys?

It’s late. You need the bathroom, but it’s so difficult to get out of bed. Everything is so uncomfortable. Everything is so difficult. Why is it all so difficult? Still, you manage to find your way to the bedroom door, then stumble into the hallway. Very quickly, the others materialize, as if from nowhere. Hands are holding you up, but you try to shrug them off. You don’t need their help. You would like to be left alone. Is it so much to ask, to be able to use the bathroom alone?

Mother, one of us needs to be in here with you.

Nonsense, you try to say, but it doesn’t come out quite right. I just need the TV, you say.

You get a puzzled look. The TV?

I need to use the TV.

They look at each other. Mother, the TV is in the other room. If you would like to watch TV, we can do that with you. But if you need the bathroom, one of us has to help you.

The indignity of it all makes you want to scream. I am your mother! I wiped your bottoms when you were little! But all that comes out is an incoherent mashup of words, and that just adds to your frustration.

When you came to this country, in 1969, 36 years old, with four children, the youngest’s age still measured in weeks, you were highly dependent upon your husband. He was older, wise in the ways of the world, a handsome ship’s officer and rising star in the maritime industry. He swept you off your feet fifteen years earlier, and now he had brought you to the far side of the world. You had always treasured your own self-reliance, yet in 1969, even with air travel, New Zealand seemed very far away, and the United States was a foreign country, even if something of a magical destination.

Just a few years later you would be divorced. You would marry again, briefly, but that would be more of a fling than a serious life choice, though you would keep your second husband’s name as your own for the remainder of your life.

After your second divorce, it became clear that working as a secretary was not going to cut it. You could not and should not depend upon anyone else. You would need to provide for yourself.

And so you did. You put yourself through school, became an office manager for a Bay Area company manufacturing silicon wafers for these little devices that would soon power the world: integrated circuits, or chips. Already the southern peninsula, where you worked, was gaining a new name in popular parlance: Silicon Valley.

You moved through a succession of mid-level management jobs for various high-tech companies: Accurex, Intuit, Sun Microsystems. Briefly, in your mid 50s, you returned to your Antipodean roots, living in Sydney, Australia, where you were shocked to find gender and age discrimination at a level twenty years behind the United States. Your hazy golden-hued ideal of Australian and New Zealand culture became a bit shattered when interviewer after interviewer said things to you like, “Why do you want to be a manager? You’re a woman,” or “But you’re 55; you’ll just retire in a year.” As if! You were not ready to retire at 55, and what business was it of theirs?

After a few years you returned to California, rekindled your love of hiking and the outdoors, and took up an old pursuit: trail building. You reconnected with the Sierra Club, and specifically a chapter called the Sierra Singleaires, single hikers over the age of 40. Here before you had found your tribe, and they welcomed you back with open arms. Many hours, days, years, you spent repairing or building trails in local parks and forests.

After retirement, your sense of adventure renewed itself, and you enrolled with the Peace Corps. You began learning to speak Romanian, and soon you found yourself in Bucharest, helping small business owners adapt to the modern world after the fall of the Iron Curtain. And although an injury, and major surgery, forced you to cut your Peace Corps time short, it remained something you could be proud of, alongside those beautiful trails.

You scrimped, and you saved, and you lived frugally. Your only luxury was a new car every few years. You imagined yourself a sporty driver, and prior to your very last car, you never owned one that wasn’t a manual stick-shift transmission. No automatics for you! Yet despite this one luxury you allowed yourself, you managed to beat the system. You found a way to live in the heart of Silicon Valley, one of the most expensive areas on the planet, in your own home free and clear, on not much more than your Social Security check. Of course, your daughters would later fret over the state of your closet, wishing you’d allow yourself something new once in a while, but you never forgot your depression-era roots. That rainy day still might come.

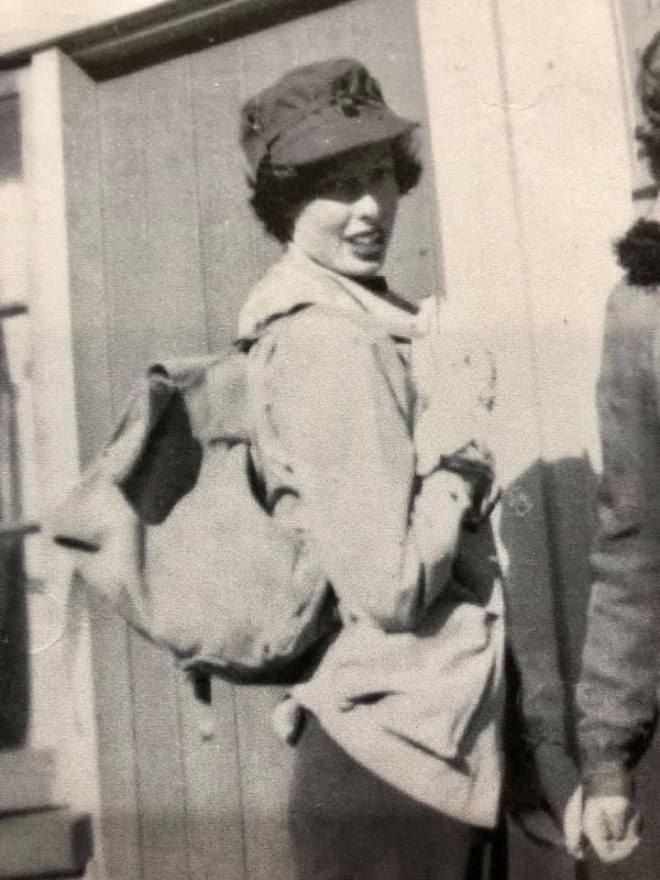

Judith Anne Hargreaves, later Judith Fraser, then Judy Kretzer, passed peacefully from this world on March 9th, 2019, approximately three weeks after being diagnosed with a large glioblastoma, a highly aggressive brain tumor that typically does not respond well to treatment. She was 85 years old. She leaves behind four children, seven grandchildren, two great-grandchildren, and a network of trails in Butano State Park, California.

header image credit: pixabay.com